Redactioneel

Click here to go to the Gidslecture 2023: ‘My Hardly English’ by Don Mee Choi.

Click here for the Gidslecture 2023 in Dutch (translated by Han van der Vegt).

I thought a long time about how to introduce Don Mee Choi, which already felt like an overwhelming task given how important her work and her mentorship have been to me as a Korean-American poet and translator. Following the results of Dutch general election on 22 November, however, I decided to introduce her first and foremost from my place as a resident of this country, the Netherlands, and as an inhabitant of the Dutch language as much as Korean and English. I want to introduce her by saying why right now, right here, we need Choi’s work more than ever.

During the 1Vandaag election debate, as Frans Timmermans – the leader of the combined leftist parties, PvdA and GroenLinks – attempted to outline how the Netherlands could become a leader in green technology and industry, Geert Wilders – leader of the right-wing PVV party – threw back in response: “weet u, u spreekt geloof ik zeven talen maar niet de taal van het volk.” You speak seven languages but not the language of the people.

There is no actual logic to this response, but the audience laughs, even Timmermans nods as if conceding it’s a good zinger, and the PVV proudly posts this on Twitter, garnering over 5000 “likes.”

But since when has multilingualism become diametrically opposed to “the language of the [Dutch] people?” In a survey conducted by the European Commission a decade ago, 94 percent of the respondents from the Netherlands said they were able to speak at least one other language beside their mother tongue, and 77 percent were able to communicate in at least two additional languages.

The Dutch people are a multilingual people, not only because of the languages they learn in high school or university (which, it must be said, is an achievement one has worked hard for and can be proud of) but because of the languages their learn through their grandparents and parents, through their favorite television programs or novels or songs, through the communities or subcultures they connect to online, through the person they fall in love with, through so many different spaces and ways.

In asserting this false, fictionalized but nonetheless powerful image of “het volk,” what Wilders does here is wield what Choi calls “order words” in her poetry collection DMZ Colony, which won the National Book Award in the U.S. “Order words” force people into oppositional categories, delineate and limit who they must be, make their identities flat, simple, legible and manipulable to authority. “Order words” insist that there is one authentic group of Dutch people, a monolithic and homogenous Dutch culture, and a monolingual nationalist mode of expression.

“Order words” are also what was imposed on a peninsula of people, the Korean peninsula, following the Second World War when they were told, “From this line on a map, you are now the North; you are now the South.” And from our perspective in the 21^st^ century, we can see that the new order that emerged wasn’t liberation and protection, as promised, but the violent and extractive clutches of neo-colonial power. For the South, specifically, it is a never-ending tribute to the U.S. brand of militarization and Capital. As Choi writes, “Order words compel division, war, and obedience around the world.”

In reading Choi’s poetry, particularly in the collections that she calls the Korea-U.S. trilogy – which includes the 2016 Hardly War, the 2020 DMZ Colony and Mirror Nation, which will come out in April 2024 – the circulatory relationship of division, war and obedience are brought sharply, poignantly and personally into focus, through an assemblage of archival photos, transcribed interviews, translated documents, and Choi’s restlessly imaginative rotations (we could even call them revolutions) of language. Fundamental to Choi’s work across different media, networks, and languages is her assertion – itself a revolution or “turning” of Walter Benjamin’s assertion – that “Translation is a Mode, Translation is an Anti-Neocolonial Mode.”

In addition to being a writer and artist, Choi is of course a groundbreaking translator, most notably of the great Korean poet Kim Hyesoon, with her translation of Kim’s collection The Autobiography of Death winning the 2019 Griffin Poetry Prize. Choi’s mode of translation, and her translation as a poetics, is radical and necessary because, as the MacArthur Foundation noted when they award Choi one of their “genius” fellowships in 2021: “Choi’s intertwined practices as poet and translator bear witness to otherwise unspeakable histories and expand the range of expressive possibilities for writers from diasporic and multilingual backgrounds.”

What Choi shows us is that translation isn’t just the bringing together of two languages, by moving a text from one to the other, but that it in fact is a mode of excavating and articulating the invisible, overlooked or suppressed colonial and racist systems that already have bound different groups of people, different cultures, together. Languages always exist in relation to each other, and always with a power dynamic between them. Translation reveals these relations; it gives us the tools through which we can critique, bend and dismantle these dynamics; and, particularly in the hands of a poet like Choi, translation can reimagine “order words” into “other words.”

As Choi writes, “But other words are possible. Translation as an anti-neocolonial mode can create other words. I call mine mirror words. Mirror words are meant to compel disobedience, resistance. Mirror words defy neocolonial borders, blockades. Mirror words flutter along borders and are often in flight across oceans, even galaxies. Mirror words are homesick. Mirror words are halo. Mirror words are orphaned words. Now look at your words in a mirror. Translate, translate! Did you? Do it again, do it!”

For example, through Choi’s “mirror words,” we learn that the syllable “이” (pronounced as /ee/) is the Korean word for, and therefore also connects together as homonyms, “teeth,” “lice,” “two” and “this.” “이” is also the expanded and slippery “i” of “ideology” and the E of “Empire.” But having learned this, we should also now realize, as Choi tells us, that, “이,” “it has other possibilities such as Earth, Equality, Internationality, etc.” Perhaps that is the most important word in this list of possibilities, “etc,” etcetera, the space reserved for Choi’s imperative to us, “Translate, translate! Do it again!”

Through Choi’s poetics, language refuses to remain fixed, it disregards imposed limits, it defies, it resists, it migrates, it takes flight. But it also does so in order to build for us a place of refuge, a nest, even if our current world won’t allow it. What is a poet, after all, but the strange citizen of the world that demands the impossible? Ultimately, the imperative and model I find in Choi’s poetics is the dogged, determined capacity for a profound and tender and, yes, capacious generosity. Choi shows me that actual liberation is, in fact, the knowledge, the faith, that we can always be more than they tell us we are.

The poet marwin vos wrote an essay on Choi for the current issue of De Gids, which really must be read alongside listening to this introduction. Here vos writes about Choi: “Ze is als een oudervogel die alles meepikt wat ze kan gebruiken voor haar taak. ‘Home’ komt geloof ik niet voor in de bundel, wel ‘homesick’, twee keer.” She is like a bird-parent that gathers anything she can use for her task. ‘Home,’ I believe, doesn’t appear in this collection, but ‘homesick’ twice.

I believe this is because the homesick are the ones who understand best of all what a home can and should be. The homesick are the ones who dream of a home and still believe in its possibility. The homesick are the ones who know what it means to belong.

“U spreekt zeven talen maar niet de taal van het volk.” And so Choi tells me, “Do it again, do it!” So I will take these “order words” and translate them into other words, “mirror words,” to say that “het volk,” whatever that is, now has to include me, and my two children, our teeth, our lice, our “this,” our “etc.” our descendants, and the memories, dreams, and languages of our ancestors, our bird-parents, we’ve brought into Dutch.

I first learned about the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s notion of “linguistic hospitality” while reading the translator’s note for Mommy Must Be a Mountain of Feathers, another collection by Kim Hyesoon that Choi translated. “Linguistic hospitality” is when “the pleasure of dwelling in the other’s language is balanced by the pleasure of receiving the foreign word at home, in one’s own welcoming house.”

Having grown up for so many years as a poet dwelling in Choi’s language, as well as Kim’s language rendered into Choi’s language, I now say this to you sincerely, entirely, not hardly: it is one of the greatest pleasures I’ve had in life to be able – hier in Nederland, in het nederlands, in English, 그리고 한국어로, in mijn geadopteerde moederland – to welcome Don Mee Choi.

Essay

Fragmenten over pijn – uit een der persoonlijke e-mailwisselingen tussen Jan van Mersbergen en Elte Rauch

Verhaal

Verzamelde fonteinen

Beeld

documenting the body

Poëzie

Uit ons bestaan

Essay

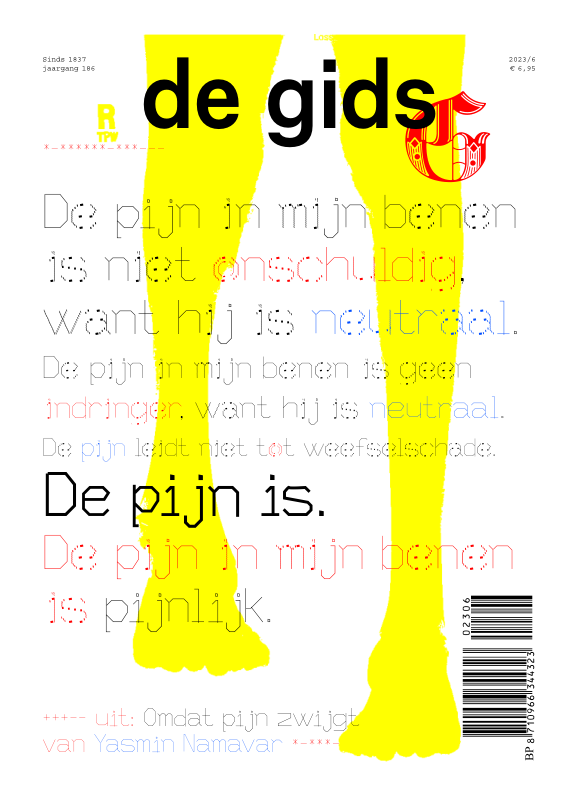

Omdat pijn zwijgt

Poëzie

zo ben ik geworden, ik had lang niks

Interview

Kerstcadeautje

Verhaal

Het eerste zonlicht

Poëzie

Een fjord van pijn

Verhaal

Een keurige leeftijd

Gidslezing

Mijn nauwelijks-Engels

Gidslezing

My Hardly English

Verhaal

Alles & Iedereen

Verhaal

Takotsubo!

Essay

Close Reading IX: je stelt voor (second line) - marwin vos

Kousbroeklezing

De kolonie mept terug

Verhaal

De achterstraten (romanfragment)

Poëzie

Mijn woestenij

Brieven