Redactioneel

Click here for the introduction to this lecture by Mia You.

Click here for the Dutch translation of this lecture by Han van der Vegt.

During the translation panel at the 2022 Stockholm International Poetry Festival, Kim Hyesoon commented to the audience and the other speakers – Jennifer Hayashida, Andjeas Ejiksson, and me – that she had nothing revelatory to say about translation, and yet she still gave us a memorable image for translation: the womb of death. She said that she had listened to the womb of death – as if she were listening to her mommy’s womb –while writing Autobiography of Death. She intently listened to the rhythms and wrote them down as poems. It occurred to me then that this is exactly what I do when I translate – I listen intently to the womb – translation womb.

Translation womb is also the womb I was separated and expelled from as a child. During the Korean War, 250,000 pounds of napalm were dropped daily by the US. Needless to say, I grew up in a holey womb.

After flailing about in homesickness for many years, I found myself tuning into the womb again through Kim Hyesoon’s poetry. Translating Kim’s poetry for the past twenty years has been an act of linguistic return. The perpetual return and farewell can fray one’s ears – its flaps and lobes – and fray one’s umbilical cord, if it hasn’t yet rotted and fallen off. Miraculously, one end of the umbilical cord is still attached, freely.

I began my rough translation of Phantom Pain Wings during my 2019 Artist-in-Berlin DAAD residency. I wanted to prepare a quick sketch of what Phantom was about –its shape, language, and sounds. But I barely had a clue about the sketch I was making. Translation language, language of womb, is often incomprehensible to me.

A while back, when I was working on All the Garbage of the World, Unite! Kim instructed me to translate the rhythm and not the meaning of her poetry. In Garbage, Kim frequently utilized duplicatives to create rhythm in her poems:

swiftswift waddlewaddling stickysticky cacklecackled draindrained lumplump gentgently dripdrips kisskissed pantspants gulpgulp stiffstiff slapslap staggerstagger floatfloat dripdrip wigglewiggling dangledangling closeclosely farfar limplimp clamclammy bangbang pukepukes gripegripe trembletremble gnawgnaw flutterflutter whackwhacked drooldrool bambam plopplop rattlerattle. stuckstuck whinewhine rollrolled whimperwhimper

These duplicatives in Korean are not unusual, but the fact that she had used them excessively throughout her collection signaled something else, something more.

It signaled trance language, a womb language. The womb instructs me. My first encounter with trance language was when my mother brought in a shaman to do an exorcism. It was nothing too elaborate, just a short rite to chase away what was ailing us in the absence of our father. It was winter, and we were all ill with fever, and my little brother broke out in hives. I already knew the shaman because she lived a few houses down from ours. She had only one breast, which frightened me. Because I was a little child, I thought that she might be half-man. Whenever I heard the loud clanging sounds of a brass gong, I peeked through the wood gate-door of her house, to watch her in a state of trance. That winter day, she floated into our main room, which was both a living room and a communal sleeping room, already dressed in her shaman costume. She began jumping around, beating her gong. We all sat, kneeling, as if we were on the shaman’s stage. I felt in my whole body the thumping of her feet and the frenzied beatings of her gong. She shouted and sang to the spirits that were invisible to us. I didn’t understand her language even though she spoke and sang in Korean. We all cried uncontrollably from the acute sadness the shaman stirred up in us. A child’s sorrow is always connected to something much bigger – perhaps a river or a mother’s amniotic sac. This inexplicable sorrow I felt then still haunts me in my dreams. When I began translating, I found myself crying again. I knew then that I had finally found my way back to the womb – the place of incomprehensible language and excessive rhythms, not only of sadness, but also of darkness, cuteness, sweetness, ratness, momminess.

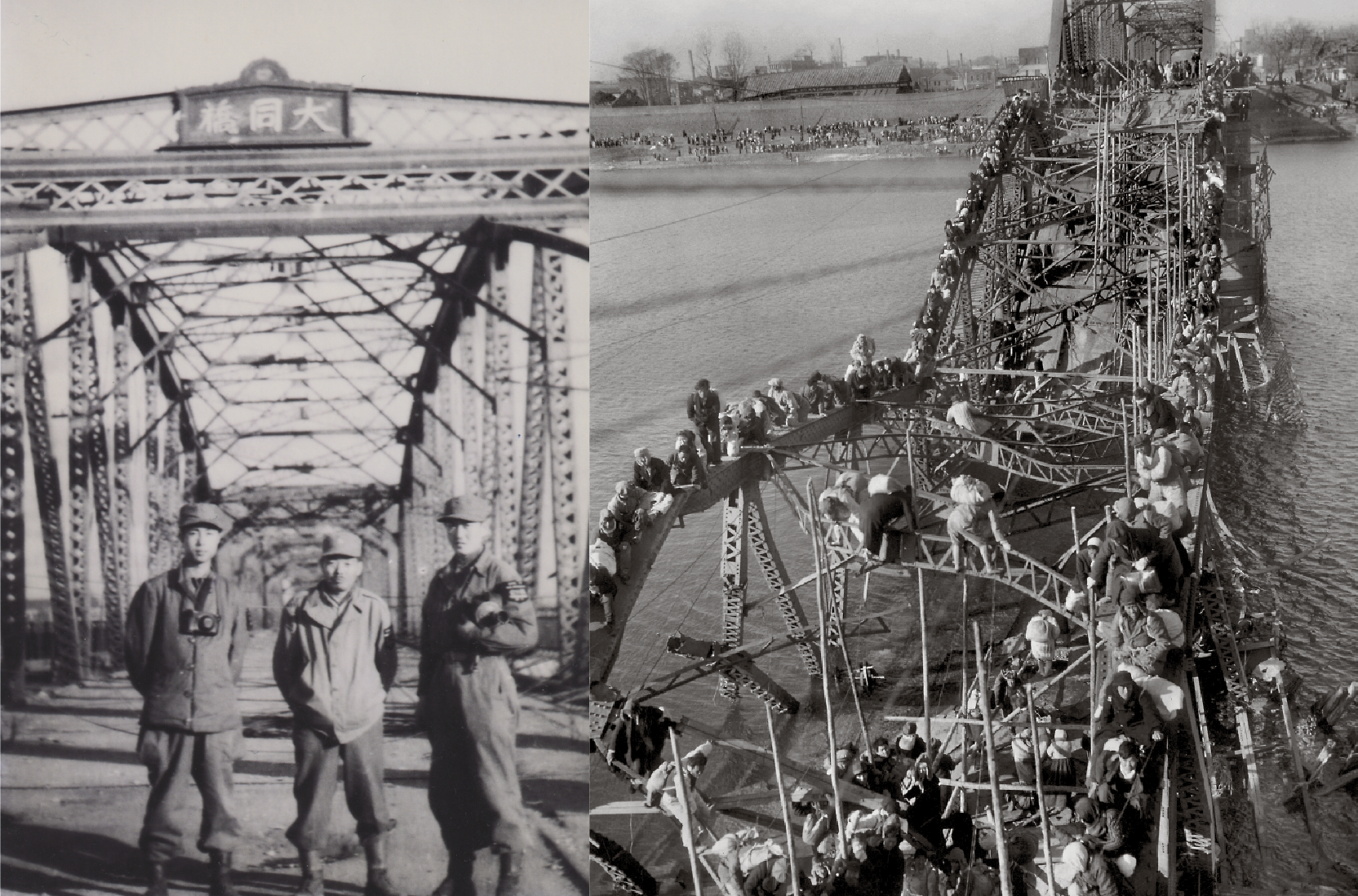

Later, when I rediscovered my father’s photographs, I followed his memory inside his camera and crossed the bridges he had been on. This led me to Hardly War in which I explore the Korean War, the unending war – because it has not officially ended – the war that is referred to as the “Forgotten War” in the US. Hence hardly. It was inevitable that I would reconnect with the language of war and its hardliness. After all, I was born out of my mother’s body that endured the war. It was my first language. Because I used to think that my father was a foreigner (because his work took him outside of Korea and I rarely got to see him), I believed that everyone inside my father’s camera were foreigners, which meant that they spoke English. For Hardly War, my task was to translate the foreigners’ English spoken inside my father’s camera. It’s the English that I had imagined as a child. My pretend English. My scribble English. My hardly English.

Don Mee Choi, Hardly War (New York & Seattle: Wave Books, 2016), 5. There are more bridge images and references in the forthcoming Mirror Nation.

I can never remember how I translate. Womb is the most intimate, unforgettable thing, yet it’s the first thing I must exit, to skip along in a rhythm I feel and hear “do and do and to” – as I did in Hardly War. After all, there are many holes through which I can exit. I follow the rhythm that is channeled from war to war, womb to womb.

In Minor Salvage: The Korean War and Korean American Life Writings[1], Stephen Hong Sohn borrows Angela Naimou’s notion of salvage, explored within the context of slavery and the Caribbean. He quotes Naimou: a “critical and creative practice that animates every encounter with the ruined, junked, and trashed…” Within the context of Korea, Sohn uses “the modifier minor to denote the limits of” his critical practice because: “Salvage can only ever be partial and unfinished, as the violence wrought by the Korean War remains unending.” After Sohn read my DMZ Colony, he emailed me to tell me: “It’s salvage.”

In my creative practice of salvage, I reanimate the discarded that remain inside my father’s camera, memory. For the past twenty years, I’ve been salvaging myself through the act of translation. I follow the rhythm that is channeled from war to war, salvage to salvage. I sing salvage. I’m salvage myself.

I returned from my residency in Berlin to Seattle just as the pandemic lockdown began. I started going over the poems of Phantom Pain Wings one by one while Covid-19 deaths kept rising. (Kim commented after she read “Translator’s Diary” I wrote for Phantom: “I felt a lot of sadness in your diary.”) At the time, I was tracking the Covid-19 deaths; tracking the ongoing violence of Empire. I was listening to the deaths and losses that came through Kim’s poems. These forces all merged and set the tone for Phantom. I also realized that she had invented a whole new language: bird language, a language to speak the personal and collective parting. It was very difficult to decipher this bird language – it was difficult to know who the speaker even was. I felt utterly disoriented and incompetent, as I often do.

In Korean, subjects don’t have to be explicitly stated. They can be inferred accurately, most of the time, within the context of a sentence or passage. But somehow the subjects in Phantom were more than implied because they were not clearly definable. The subject’s identity was more complicated. The subject was human and not human, bird and not bird. The guitar was not simply a guitar. After several email exchanges, Kim and I agreed to state the subjects explicitly at times as “I + bird” or “I + bird + music” or “I + guitar.”[2] Kim Hyesoon’s “I-do-bird” phenomenon[3] demands “+” the way, in translation, womb demands womb. The way, in salvage, salvage accumulates like garbage:

Sweetpotatokneesappleseedgod. Pigstoenailschickgod.

Dreamingdivingbeetlesashtreegod. Lovelygirlsheelstoenailgod.

Antsghostscatseyeballgod. Ratholescatsrottingwatergod.[4]

Within the patriarchal womb, Kim has always observed trash and women, intently. They’re inseparable:

Oh what’s wrong with this woman? People. Passing by.

You’re a piece of discarded trash. Garbage to be ignored.[5]

Women and trash pile up. When I wake up from my salvage act, the only thing I remember is wombwomb. I don’t want to remember garbage. Because once upon a time, I was a garbage girl. I was found abandoned under the Hangang Bridge, and a young, kind woman took pity on me, and she nursed me and raised me. The kind women of my family told me this story often, as a warning that girls can be thrown out at any moment, and that baby girls are often found as “a piece of discarded trash.” Minor, indeed. Hence, I “merely merrily washed my face in the yard and looked up at the stars.” There’s no doubt in my mind that I’m still a garbage girl. We sing together: wombwomb. Someday, when I stop translating, I’ll finally turn into “garbage to be ignored.” This is why girls must sing salvage till they drop dead.

This spring, I wrote to Mia You and told her that for this talk, I wanted to trace the birth of my English. Mia and I are linked by the same river, Hangang, which is fed by a river from the South and the North, flowing through Seoul. So at one point, we must have drunk from the same river, and our amniotic sacs are filled with the same river water. In 2000, the US military, from its former Yongsan base in Seoul, dumped formalin into the sewer system connected to the river. I can confidently say that the rats of Seoul were the first to bathe in formalin before the vinegary-smelling solution reached the river. (Once, I had a dream about Kim Hyesoon’s rats – they were impervious to the poison that glowed like an emerald.) Inside the militarized, contaminated amniotic sac, we may be pristinely preserved, like princesses, unable to rot. Hangang’s mouth opens to the Yellow Sea that meets the border along two Koreas. Its exit is prone to US-ROK military exercises. What can a divided tongue say? Yankee go home!? Princess Rats squeal: “O-Yankee-bon-bon!”[7]

Prior to my exit or expulsion from the womb, I knew a real English word, which can be thought of as “The New American Word”[8]: Hello. I heard different variations of it while growing up: 핼로/Hello, 할로/Hallo. I knew the new American word not as a greeting, but as a noun. A noun for an American GI. It was translated into a noun by those who lived through the war, such as my mother, her sister, my grandmother, and all the women who had to hide from the troops of nouns. I remember waving with my friends, ecstatically, at an American GI, who happened to walk through the narrow alley of our neighborhood. Why did the new American word make me so ecstatic? Princess Rats, by nature, are ecstatic, unable to stop squealing, hissing, and cackling: O-pickle-bon-bon!

After the war, women who needed to survive and ensure the livelihood of their families fell under the patriotic duty of KOR-US binational military prostitution. The women were given a derogative name: 양공주 yanggongju. The first syllable 양 “yang” means “western,” and it sounds like the first syllable of Yankee. Hence, Yankee Princess. They were exclusively for American GIs. Because most were born as Princess Rats, Yankee Princesses are also, by nature, ecstatic, unable to stop squealing, hissing, and chattering:

Tell the world

We want

Coty powder!

…

O totally tether!

Does it tatter?

…

O patter matter!

Do you batter?[9]

In 1972, after we bid farewell to our relatives, my family landed in Hong Kong. There were no direct flights to Hong Kong from Seoul then, so the plane landed in Tokyo-Narita Airport to refuel. The date of our exit was July 7th. The same day when the once-upon-a-time, star-crossed lovers Jiknyeo (Weaver) and Gyeonwu (Cow Herder) are allowed to meet. Magpies and crows fly up to form a bridge across the celestial river Milky Way so the parted lovers can meet briefly. The rain that falls on July 7th are the tears shed by the Weaver and the Herder. It didn’t rain the day we landed at night in Tokyo, but we were enveloped by thick fog. I could barely breathe in it. I thoroughly regretted singing “Angae” [Fog], a sad love song for grown-ups that was very popular in the 60s. Now I was trapped inside the fog of longing and farewell. Somehow we made it out of the blanket of fog and landed in Hong Kong, an island without a midnight curfew. It was like heaven. The endless twinkling city lights made me think that I was crossing the Milky Way.

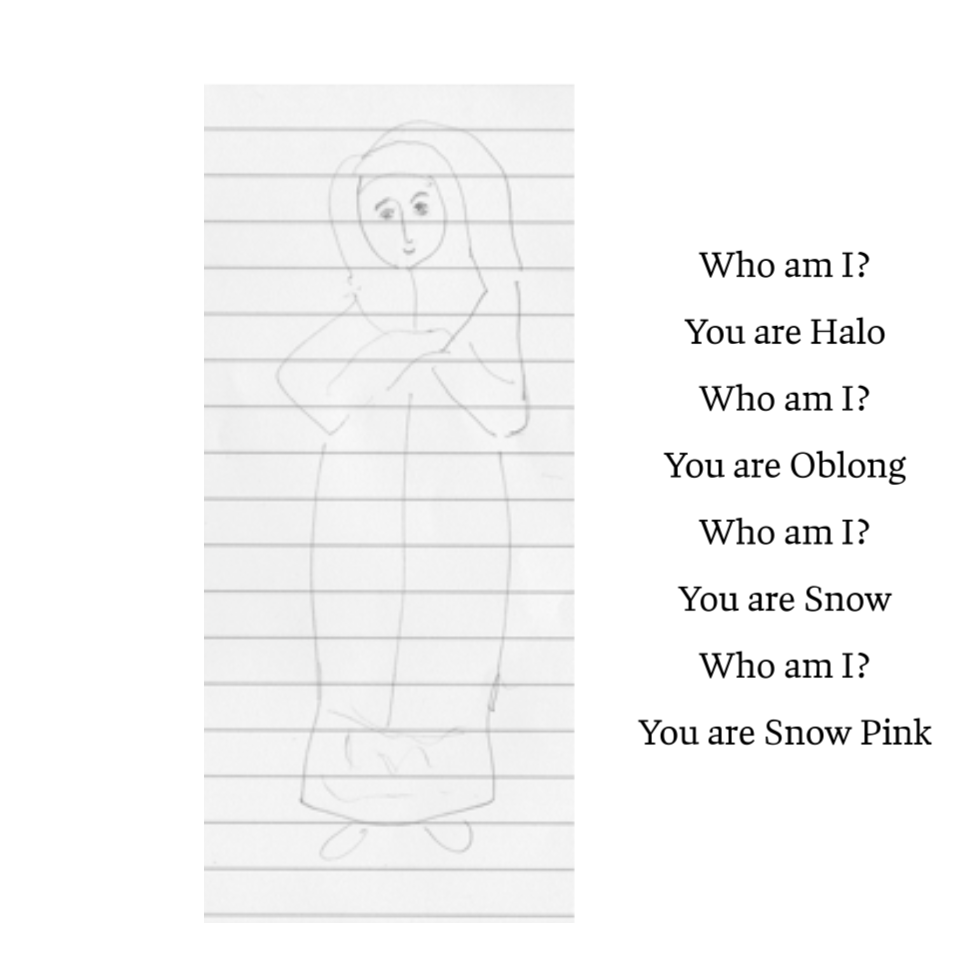

Perhaps because of the rattiness of my ears, I had a hard time differentiating Korean and English from one another. I convinced myself that I could learn English by paying attention to the overlapping sounds between Korean and English. So the variations of Hello and other nouns kept growing: 헤일로/Halo, 홀로 [alone]/Hollow, 이 [lice, teeth]/e, and오/5/zero. The number 5 in Korean that sounds like zero or Oh/O in English never failed to rattle me. Every time I heard these conjoined, translingual words, I froze, like a rat under the beam of a flashlight.

Eventually, I became an adult rat and swam across the Pacific Ocean to the US and forgot that I ever was a rat. I must have left my tail somewhere deep inside the fog. Later on, probably not accidentally, I came across the tales of my fellow rats in many of Kim Hyesoon’s poems:

A rat

devours a sleeping white rabbit

Dark blood spills from the rabbit cage

A rat devours a piglet that has fallen into a pot of porridge (chunks of freshly grilled flesh inside a womb,

babies that shiver from their first contact with air,

fattened chunks of flesh,

tasty, warm chunks that bleed when ripped into)

A rat devours the newborn in the cradle

Mommy has gone to the restaurant to wash dishes

A rat slips in and out of a freshly buried corpse[10]

The relentless fire bombing during the war couldn’t kill all the rats. Rats persisted as gooks, dressed in white pajamas. In Hardly War, I was finally able to reconnect with my rubbish English, in other words, my me=gook language. 미국/America. 미 (sounds like me) means beauty and 국 (sounds like gook) has multiple uses and meanings in words such as nation, hydrangea, and radish soup. I know gooks look all alike, and they even stick together like trash, hence my glossary:

미=국 수=국 무=국 화=국 애=국

Beauty=Gook Hydrangea=Gook Radish=Gook Flower=Gook Love=Gook

무궁화=5 petals[11]

I tried to overcome my fear of the sound오/O/5/0 zero[12] –believe me it wasn’t easy. It’s like asking Princess Rat to get over her fear of real princesses. So I scribbled in pretend English like I did as a child, waiting for my father to return home from Vietnam. Suddenly, I had a litter of O words:

O-Pinkville O-like-me O-like-me O-seaweed O-sway-me sway-me O-like-me O-told-me O-a-like-a-like-a O-crazy-daisy! O-ring-spots! O-orphans! O-a-like-a-like-a O-now O-bonnet! O-rose-of-sharon! O-lily-bang-bang! O-lily-me O-flower! O-flower! O-blouse O-ribbon-bon-bon O-orphans! O-bonnet-bon-bon! O-pajamas! O-bon-bon O-bad-guy OK-bang-bang! O-Yankee-bon-bon! O-bonnet! O-Ok-bon-bon O-scribble! O-lily-pomp-pomp O-Daddy! O-starched! O-petti-Coty! O-petti-coup! O-rosy-posy! O-Coty-hoity! O-bridal-shoes! O-news! Excuse me! O-belt! O-petti-coup! You may powder! Overly ovaries! How overly! O-Lily-Sir! O-Petti-Sir! O-Coty-Sir! O-Powder-Sir! O-Tiger-Sir! O-Pomp-Pomp-Sir! O-doodle! O-him! O-mayhem! O-Seaweed! He smiled! O-parade-you-are-my-foreign-aid! O-Colony! O-Neocolony! O-Overly! O beauty Colony! O potty! O-beauty-of-publicity![13]

I think about how hello-hallo-halo-hollow predates the birth of a salvage girl, which is to say she was born into me=gook language, and if I were to follow the logic O-Neocolony!, then it wouldn’t be too far-fetched to say that I was born with a halo. Mia too. And because we were born in the land occupied by the troops of nouns, “in reality, we were all motherless.”[14]

[15]

And yet, we were not 홀로/hollow alone. Hello was always with us. Hello go home!

Park Chan Wook’s film Decision to Leave (2022) swept me back into the fog I encountered during our transit to Hong Kong and the song “Angae” I sang as a child. Decision consists of layers of cinematic, literary, and musical referents: the song “Angae;” the older, masterful film Angae/The Foggy Town (1967) by Kim Su-Yong; and the short story “무진기행” [Record of a Journey to Mujin] [16] by renowned writer Kim Seung-ok, which The Foggy Town is closely based on. The story is understood as emblematic of the post-war, 1960s military dictatorship era. Despite the erasure of the violent neocolonial history of Korea during the dictatorship, war memory and war trauma still persist in the mind of the protagonist who has returned to his hometown Mujin for a brief visit. What took me by surprise was that Yankee Princesses appear prominently in both the story and the older film. Shoeshine boys surround the “crazy woman” and taunt her:

“공부를 많이 해서 돌아 버렸대.” “아냐, 남자한테서 채여서야.” “저 여자 미국 말도 참 잘한다.”

“She’s gone mad because she studied too much.” “No, it’s because she’s been jilted by some man.” “The woman can also speak American really well.”[17]

She knows the troops of nouns intimately, and, like me, she knows me=gook language.

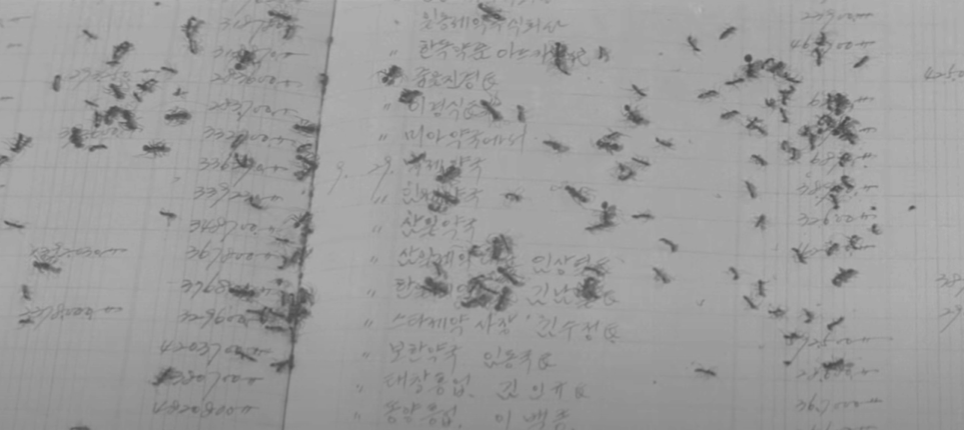

In Decision, Park evokes The Foggy Town with the image of ants. The ants of The Foggy Town swarm the open ledger of the protagonist. The ants of Decision swarm the face of a dead man with his eyes still open. For me, one of the most daring, magnificent cinematic moments in Decision is when Park inverts the scale of the ants by depicting the outside world from the inside of the dead man’s open eye. The ant is no longer tiny, but huge, as if swirling inside a flimsy sac, and the detectives standing on the peak in the background, where the dead man had fallen from, now appear as tiny as ants. This inversion sets a stage for the film’s memory of The Foggy Town. The inversion magnifies.

Kim Su-Yong uses the ants to depict the irritable, erratic mind of the protagonist and also the insignificance of human lives under the military dictatorship. In one of the flashback scenes, the protagonist as younger-self is dressed in dark shirt and pants, and on his back, he squirms in anguish, like a helpless insect, unable to bear the isolation and shame of hiding at home during the war. His mother prevents her only son with tuberculosis from going out to the front line to fight and die as war trash. In another scene, the protagonist walks side by side, conversing with his younger, insect-self. His salvage self. In The Foggy Town, the inversion takes place through exquisite, poetic long shots in which humans appear as tiny as ants. The long, distant shot magnifies the insignificance.

안개 [The Foggy Town], directed by Su-Yong Kim (1967). A screen shot.

Decision to Leave, directed by Chan-wook Park (2022). A screen shot.

안개 [The Foggy Town]. A screen shot.

Park is able to speed up and magnify the insignification process thanks to 21^st^ Century technology. In Decision smartphones play a vital role as the medium of translation between the protagonist Detective Jang and the murder suspect Song, an ethnic Korean from China. In the story “Record of Journey to Mujin,” fog functions as the magnifier of war memory. The dense fog acts as a memory cloud. While the memory cloud in The Foggy Town replays desolation and meaninglessness under dictatorship, the smartphones in Decision play back intimate dialogs between Jang and Song and translate Song’s narration of grandfather’s historical past, restoring memory and meaning. Song, who arrives in the port of South Korea as a stowaway in a shipping container, is a granddaughter of an anti-colonial fighter who resisted the Japanese imperial forces during the colonial era (and very likely also during the Korean War, against the US neocolonial occupation). Smartphones in Decision restore the memory of anti-colonial history erased during the dictatorship.

Detective Jang finds Song’s use of Korean language irresistible. She uses old-fashioned? but poetic sounding expressions such as 단일 [solitary], 마침내 [at last], and 현대 사람 [modern man]. He tells her, “You speak Korean better than me,” and amuses himself with the thought that she must have picked up the words from watching Korean historical TV dramas. However, there is one key word Song learns on her smartphone when she listens to a recording of the detective confessing his feelings for her: 붕괴 [destroyed]. She learns that the detective has been shattered by his feelings for her. She listens repeatedly to the recording of Detective Jung, confessing his crazed state of mind in full intensity – like ants swarming, like the young man squirming. Song, ultimately, translates his shattered state as his love for her. Song is now the anti-colonial translator, not the smartphone. Solitary hollow words have the power to salvage or destroy, or both at once.

Decision to Leave. Screen shots.

Now the granddaughter of an anti-colonial fighter must find her exit, the exit out of the magnifying fog, the memory cloud. Now that she has learned that she is loved, she longs for her exit, to make her decision to leave. To leave not as stowaway garbage but as self-determined salvage. On the beach, she digs herself a hole. Her exit is armed with a blue-green bucket and blue-green fentanyl pills.

I couldn’t shake off the fog and the haloness of that solitary word. Destroyed. A child’s exit is no less shattering. Merely merrily. My father was once armed with cyanide during the war. So were the “bar women” who speak me=gook language really well, but choose to exit Mujin in The Foggy Town. Song’s blue-green exit feels particularly unbearable to me. It could be the accumulative effect of insignification. Then I remembered a poem I once translated, “모래 여자” [Sand Woman] by Kim Hyesoon. 모래/Sand in Korean sounds exactly the same as the word 모레 as in 내일모레 [the day after tomorrow]. I console myself with the future woman, the future of exit, the future of translation, with my hardly english.

Sand Woman

The woman was pulled out of from the sand

She was perfectly clean—not a single strand of her hair had decomposed

They say the woman didn’t eat or sleep after he left

The woman kept her eyes closed

didn’t breathe

yet wasn’t dead

People came and took the woman away

They say people took off her clothes, dipped her in salt water, spread her thighs

cut her hair and opened her heart

He died in war and

even the country parted somewhere farfar away

The woman swallowed her life

didn’t let out her breath to the world

Her eyes stayed closed even when a knife blade busily went in and out of her

People sewed up the woman and laid her in a glass coffin

The one she waited for didn’t arrive, instead fingers swarmed in from all directions

The woman hiding in the sand was pulled out

and every day I stared vacantly at her hands spread out on paper

I wanted to get on a camel and flee from this place

In every dream the woman followed me

and opened her eyes

the desert inside her eyelids was deeper and wider than the night sky

[1] Stephen Hong Sohn, Minor Salvage: The Korean War and Korean American Life Writings (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2022), 17.

[2] Hyesoon Kim, Phantom Pain Wings, trans. Don Mee Choi (New York: New Directions, 2023), 32-36.

[3] Hyesoon Kim, Phantom Pain Wings, 11.

[4] Hyesoon Kim, All the Garbage of the World, Unite!, trans. Don Mee Choi (Notre Dame, Action Books, 2011), 29.

[5] Hyesoon Kim, Autobiography of Death, trans. Don Mee Choi (New York: New Directions, 2018), 9.

[6] Choi, Hardly War, 11.

[7] Choi, Hardly War, 67

[8] Choi, Hardly War, 18. “The New American Word” is from The Manchurian Candidate (film, 1962).

[9] Choi, Hardly War, 81.

[10] Hyesoon Kim, Poor Love Machine, trans. Don Mee Choi (Notre Dame: Action Books, 2016), 42.

[11] Choi, Hardly War, 5.

[12] Further puns, visual and sonic, are explored in Mirror Nation.

[13] Choi, Hardly War, 58-87. These are all the O words against the US-backed dictatorship and war in “Hardly Opera

[14] Don Mee Choi, DMZ Colony (New York & Seattle: Wave Books, 2020), 116.

[15] Choi, DMZ Colony, 70-71.

[16] Seung-ok Kim, 무진기행/Record of a Journey to Mujin, trans. Kevin O’Rourke, Bilingual Edition: Modern Korean Literature 006 (Seoul: Asia Publishers, 2014).

[17] Kim, 무진기행/Record of a Journey to Mujin, 22. My translation.

[18] Hyesoon Kim, Garbage, 2-3.

Essay

Fragmenten over pijn – uit een der persoonlijke e-mailwisselingen tussen Jan van Mersbergen en Elte Rauch

Verhaal

Verzamelde fonteinen

Beeld

documenting the body

Poëzie

Uit ons bestaan

Essay

Omdat pijn zwijgt

Poëzie

zo ben ik geworden, ik had lang niks

Interview

Kerstcadeautje

Verhaal

Het eerste zonlicht

Poëzie

Een fjord van pijn

Verhaal

Een keurige leeftijd

Gidslezing

Mijn nauwelijks-Engels

Verhaal

Alles & Iedereen

Verhaal

Takotsubo!

Essay

Close Reading IX: je stelt voor (second line) - marwin vos

Kousbroeklezing

De kolonie mept terug

Verhaal

De achterstraten (romanfragment)

Poëzie

Mijn woestenij

Brieven

Briefwisseling Maria Barnas & Niña Weijers

Essay