Redactioneel

By now it may well be impossible to add any sensible or proper words to all the millions that have been written and spoken about the life and cruel death of John F. Kennedy.

Those of us who have ever sat down to write a letter of condolence to a close friend know what an aching task it is to say something that is pointed and that touches the right vein of sympathy. But I hope you’ll understand that there is no other thing to talk about. Not here. Three thousand miles away, it may be easier to speculate about policy, the new administration. Not here. For I cannot remember a time, certainly in the last 30 years, when the people everywhere around you are so quiet, so tired looking and, for all the variety of their shape and colour and character, so plainly the victims of a huge and bitter disappointment.

That may sound a queer word to use, but grief is a general term that covers all kinds of sorrow. And I think that what sets off this death from that of other great Americans of our time is the sense that we’ve been cheated, in a stroke, by a wild but diabolically accurate strike of the promise of what we had begun to call the ‘Age of Kennedy’.

Let me remind you of a sentence in his inaugural address when he took over the presidency on that icy day of 20 January 1961. He said, ‘Let the word go forth from this time and place to friend and foe alike that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed. Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.’

This is of course the finest rhetoric, worthy of Lincoln, but what made it sound so brave and rousing on that first day was the clear statement that a young man was speaking for a new generation. It concentrated in one scornful sentence the reminder that the old men who had handled the uncertain peace in the second war had had their day and that there was at hand a band of young Americans ready not to ignore the wisdom of their forefathers, but, if need be, to fight for it.

It would be hard to say more bravely, or more exactly, that it was a fresh America that would have to be negotiated with, but that, as always, liberty itself was not negotiable.

Now, even in the moment of knowing that the promises of an inaugural address are bound to have a grandeur very hard to live up to the morning after, this remarkable speech, which the president had hammered out sentence by sentence with his closest aide and companion Theodore Sorensen, did strike a note to which the American people and their allies everywhere responded with great good cheer.

Of course we know – older men and women have always known what in their youth they blithely rattled off as a quotation from Shakespeare – that golden lads and girls all must, as chimney sweepers, come to dust. But it’s always stirring to see that young people don’t believe it. We chuckled sympathetically then at the warning which Senator Lyndon Johnson had chanted all through the campaign, that the presidency could not safely be put in the hands of a man who has ‘not a touch of grey in his hair’. John Kennedy had turned the tables triumphantly on this argument by saying, in effect, that in a world shivering under the bomb, it was the young who had the vigour and the single-mindedness to lead.

If we pause and run over the record of the very slow translation of these ideals into law – the hairbreadth defeat of the medical care for the aged plan, the shelving (after a year of strenuous labour) of the tax bill, the perilous reluctance of the Congress to tame the negro revolution now with a civil rights law – we have to admit that the clear trumpet sound of the Kennedy inaugural has been sadly soured down three short years.

Any intelligent American family sitting around a few weeks ago would have granted these deep disappointments, and many thoughtful men were beginning to wonder if the president’s powers were not a mockery of his office, since he can be thwarted from getting any laws passed at all by the simple obstructionism of a dozen chairmen of Congressional committees, most of them by the irony of a seniority system that gives more and more power to old men who keep getting re-elected by the same states, most of them from the south.

But that same American family sitting around this weekend could live with these disappointments, but not with the great one, the sense that the new generation born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage, unwilling to witness or permit was struck down lifeless, unable to witness or permit or not to permit anything.

When it’s possible to be reasonable, we will all realise, calling on our everyday fatalism, that if John Kennedy was 46 and his brother in his late thirties, most of the men around him were in their fifties and some in their sixties, and that therefore we fell for a day or two in November 1963 into a sentimental fit. However, we are not yet reasonable. The self-protective fatalism, which tells most of us that what has been must be, has not yet restored us to the humdrum course of life.

I’m not dwelling on this theme – the slashing down in a wanton moment of the flower of youth – because it’s enjoyable, or poetic to think about. It seems to me, looking over the faces of the people and hearing my friends, that the essence of the American mood this very dark weekend is this deep feeling that our youth has been mocked and the vigour of America for the moment paralysed.

It is, to be hard-hearted about it, fascinating, when it’s not also poignant, to see in how many ways people and things express the same emotion. Many of the memorial photographs in the shop windows have small replicas of the presidential standard on one side and the Navy flag on the other, recalling the incredible five days’ gallantry on that Pacific Island which Kennedy himself never recalled except to the men who were with him and survived.

A young socialite whose life is a round of clothes and parties and music bemoans the fact that the Kennedys will leave the White House and take with them the style, the grace, the fun they brought to it. An American friend from Paris writes, ‘I think his death will especially be felt by the young for he’d become for them a symbol of what was possible with intelligence and will.’ An old man, wise in the ups and downs of politics, says, ‘I wonder if we knew what he might have grown to be in the second term.’ A child with wide eyes asks, ‘Tell me, will the Peace Corps go on?’

There’s another thing that strikes me, which is allied to the idea of a young lion shot down. It is best seen in the bewilderment of people who were against him, who felt that he had temporised and betrayed the promise of the new frontier. One of them, a politically active woman, rang me up, and what she had to say dissolved in tears. Another, a veteran sailor, a close friend and a lifelong Republican, said to me only last night, ‘I can’t understand. I never felt so close to Kennedy as I do now.’

This sudden discovery that he was more familiar than we knew is, I think, easier to explain. He was the first president of the television age; not as a matter of chronology, but in the incessant use he made of this new medium. When he became President Elect, he asked a friend to prepare a memorandum on the history of presidential press conferences. He wanted to know how much the succession of presidents since Wilson had been able to mould the press conference, and how much it had moulded them.

What he received was a plea disguised as a monograph to abandon Eisenhower’s innovation of saying everything on the record for quotation and letting the conference be televised. The President Elect looked it over at his usual rate of about a thousand words a minute, granted the argument, but said simply, ‘Television is now the main personal link between the people and the White House. We can’t go back.’

He allowed his press conferences to be televised live. He also made another decision which ran counter to the wisdom of all incumbent presidents: no man who’s in power invites a debate with an opponent who is out of power and who can speak not of the things he’s done, but of the things the incumbent has done wrong. In spite of knowing well that next time he would be the man with his back against the wall, the president decided that the television debate was now an essential element of a presidential campaign.

So for three years and more, we’ve seen him at the end of our day on all his tours, in Vienna, in Dublin, in Berlin, in Florida, Chicago, Palm Beach, in (alas) Dallas; in his own house talking affably with reporters, rumpling up the children, very rarely posing, always offhand and about his business; talking to foreign students in the White House garden, making sly, dry jokes at dinners; every other week fencing shrewdly (and often brilliantly) with 200 reporters; and sometimes at formal rallies, stabbing the air with his forefinger and bringing to life again, in his eyes and his chin and his soaring sentences, the old image of the young warrior who promised the energy, the faith, the devotion that will light America and all who serve her.

The consequence of all this is that the family, the American family, has been robbed violently and atrociously of a member.

When Roosevelt died, the unlikeliest people – the very young who thought of him as a perpetual president, and some of the very old who hated him – confessed that they felt they had lost a father. Today millions of Americans are baffled by the feeling, which seems to have little to do with their political loyalties, that they have lost a brother, the bright, young brother that you’re proud of; the one who went far and mingled with the great and had no side, no pomp, and in the worst moments – the Bay of Pigs – took all the blame; and in the best – the Cuban Crisis – had the best sort of courage, which is the courage to face the worst and take a quiet stand.

This charming, complicated, subtle and greatly intelligent man, whom the Western world was proud to call its leader, appeared for a split second in the telescopic sight of a maniac’s rifle and he was snuffed out. In that moment, all the decent grief of a nation was taunted and outraged, so that along with the sorrow there is a desperate and howling note across the land.

We may pray on our knees, but when we get up from them we cry with the poet, ‘Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.’

This transcript was typed from a recording of the original BBC broadcast (© BBC) and not copied from an original script. Because of the risk of mishearing, the BBC cannot vouch for its complete accuracy.

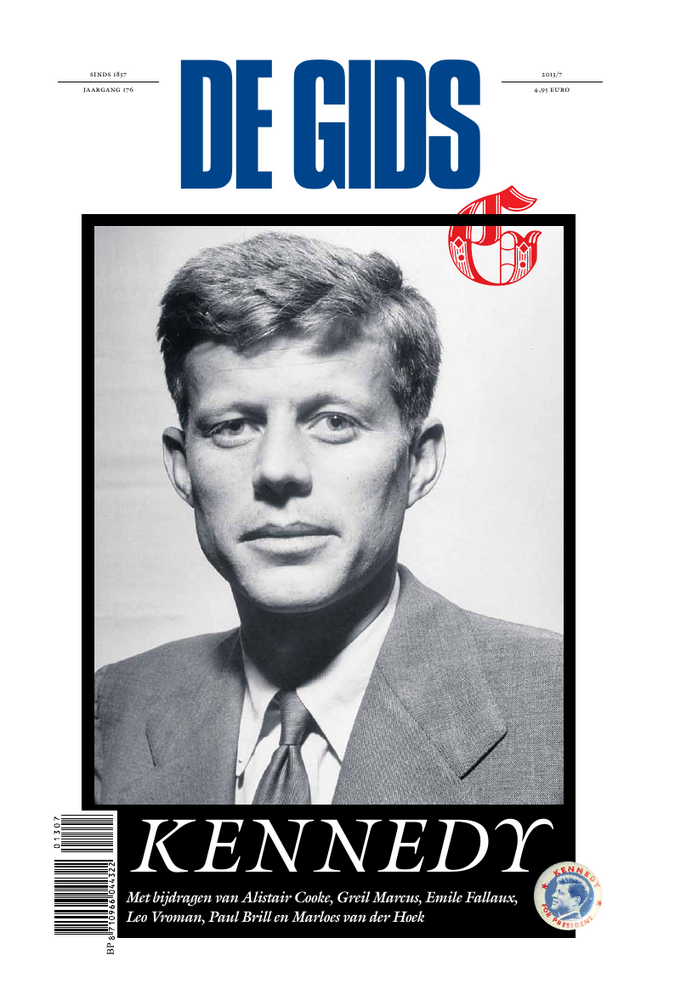

Twee dagen na de moord op J.F. Kennedy, op 24 november 1963, 21 uur lokale tijd, sprak de legendarische Britse correspondent Alistair Cooke (1908-2004) bovenstaand in memoriam uit voor de BBC-radio.

Essay

‘It Wasn’t You or Me’*

De internet gids

Brief uit Brooklyn

De ultieme beproeving

Wilde wijnruit

Een ogenblik van zwakte

Poëzie

Op uitnodiging

De internet gids

De stuurloze stad

Het geheugen en de processor

De school

Kroniek & Kritiek

Kameraad De Vries

Essay

Bedrieglijk spel

Shining India, de keerzijde

Democratie, gelijkheid en markt

Denken in tweespraak: van Diderot tot Sloterdijk

Poëzie

Ik zou mij schamen

Poëzie